There is lot of interest in surrogate measures of wound outcome to capture important aspects of treatment beyond closure. Because it provides insight into the patient’s experience, Quality of life (QOL) is an obvious surrogate for healing rate. For your own safety, don’t ask me about wound related QOL because, as we say in Texas, “Them’s fightin’ words.” I will explain why.

In 2015, the US Wound Registry (USWR) became a CMS-recognized Qualified Clinical Data Registry (QCDR). While the average QCDR costs $10 million to launch, we received less than $60,000 in contributions to the 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, nearly all of it from a Nestle grant. We wanted the measurement of wound-related QOL to be among our first CMS-recognized quality measures, but it costs money to license validated tools and we didn’t have any. In exchange for very reasonable license fees, the USWR agreed to provide the developer with the data needed for clinical validation of the Wound Related QOL (w-QoL), which we licensed from the Institute for Health Services Research in Dermatology and Nursing (IVDP) in Hamburg, Germany (click here for a copy of the “American English” version we helped develop). When CMS approved the USWR quality measure targeting wound-related QoL, we were excited.

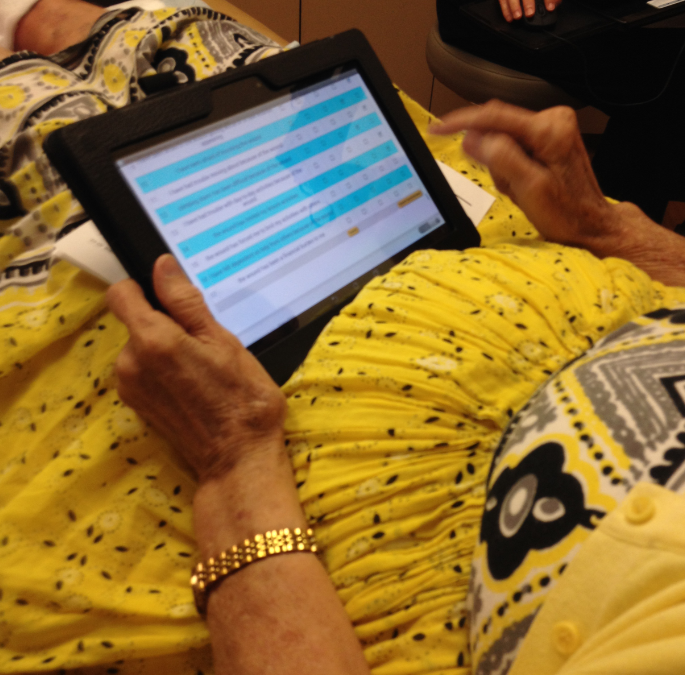

We programmed 3 electronic tablets to offer the w-QoL so that patients could answer the questions without anyone having to do secondary data entry. You may think that this would not have worked well with elderly patients. The photo at the top of the page depicts the very first patient to take it, a lady in her 80’s with rheumatoid arthritis. Her complaint was that the resolution on our low-budget tablets was not as good as her iPad at home.

The tablets transmitted the w-QoL data to the USWR, where it was later “married” with their electronic health record data. More 500 patients were administered the w-QoL during their initial visit, and of those, 100 patients received it again on the date of their discharge. I’ve attached a partial list of the clinical parameters in the de-identified dataset we provided to the developers. Unfortunately, just as we could not get funding to do the project, the Hamburg group couldn’t get funding to analyze the data. It was 4 years before they managed to perform the analysis. (A manuscript is currently under review).

In the meantime, CMS rejected the USWR wound-related QOL quality measure. Their logic was that simply administering the QOL questionnaire was not a “quality activity.” CMS wanted a quality measure that targeted a specific percentage improvement in QOL as a result of treatment. Unfortunately, we could not develop a quality measure like that unless the w-QoL data were analyzed and we could determine whether it would work. Out of curiosity, we ran some correlation coefficients on various aspects of the clinical data in relation to the w-QoL questions. As you can see from the two graphs depicted below, they appear to have been plotted by a 12-g shotgun full of 00 buckshot. The QOL questions did not correlate with any clinical wound outcome, as later statistical analysis proved.

Here are the reasons I believe that Quality of Life failed miserably as a surrogate endpoint for patients with chronic wounds (at least with the tool we used):

- On average, patients had 3 wounds which resolved and developed on different time schedules. Even when we used total surface area and total number of wounds, there was no correlation.

- As is typical, patients had an average of about 10 serious comorbid conditions. It’s likely that those underlying diseases were major drivers for their QOL scores. That doesn’t mean wound(s) don’t contribute to their misery, but if your QOL is largely determined by your severe congestive heart failure, it’s hard to identify the separate impact of your leg wounds.

- Many patients express REGRET that they are being discharged. I know you have heard your patients say, “I actually like coming here even though I don’t like having a wound.” Many of our patients get little social interaction outside of the clinical setting. I don’t know if this impacted the results, but many patients who took the discharge w-QoL were SAD about being discharged.

- The QOL questions seem logical but they pre-suppose that patients can walk, climb stairs, have social and/or intimate relationships, or take vacations. Sadly, many of our patients can’t do any of those things.

- Even the question about wound odor didn’t correlate with the clinical observations of wound odor in the chart. I have some guesses about that, including the fact that the clinicians’ nose is always right up next to a messy dressing, but the patient’s ability to smell their wounds is variable.

I think I have figured out a solution that is better than a traditional QOL approach, but that’s a topic for another day. Meanwhile, at least once a month, some unsuspecting manufacturer asks me if the USWR has quality of life data and is shocked and disappointed that we don’t. My answer is, “You need to be wearing body armor to talk to me about wound-related QOL.” Because if you don’t care enough to pay for it, you don’t really care about it.

Partial list of clinical factors evaluated in relation to wound-related QOL:

- Wound-QoL initial and final

- Age of largest wound (days) on the day of the initial and final QOL

- Wound Outcome of largest wound on the final QOL

- Surface area (SA) of the largest wound on the day of the initial and final QOL

- Total surface area of all wounds at initial and final QOL

- Wagner Grade or NPUAP stage (if applicable) on the initial and final QOL

- Total number of wounds at initial and final QOL

- Wound diagnosis of largest wound

- Change of SA of largest wound (positive or negative) if the wound did not heal

- Wound drainage amount at initial and final QOL

- Wound drainage type at initial and final QOL

- Mobility method for entering the clinic

- Work status: Is patient is still working

- Is wound malodorous at initial and final QOL

- Pain score (wound level or patient level) at initial and final QOL

Dr. Fife is a world renowned wound care physician dedicated to improving patient outcomes through quality driven care. Please visit my blog at CarolineFifeMD.com and my Youtube channel at https://www.youtube.com/c/carolinefifemd/videos

Odor scale needed …maybe need a canine? ????????

Odor tough to evaluate … maybe need.canine help? ????????