I recently reviewed with interest the press releases and case summaries issued by the Department of Justice (DOJ) related to individuals charged in the 2025 National Health Care Fraud Takedown for their involvement in the “skin substitutes” space.““`

With the exception of one podiatrist, all the other providers charged were registered nurses or nurse practitioners. The case summaries and charging documents alleged that these providers entered into business arrangements in which they recommended the purchasing, ordering, and/or use of certain skin substitute products billed to Medicare in exchange for “kickbacks or bribes.”

In my blog, I asked for an attorney with expertise in this area to explain it to me, and David Traskey responded. Mr. Traskey’s explanation was so enlightening that I asked him to write a guest blog to explain it to everyone. He’s the perfect person to do that, because he previously served as Senior Counsel with the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Inspector General (OIG). He is now a Partner and the co-head of Garfunkel Wild’s Washington, D.C. office, where he advises individuals and entities involved in government investigations, guides clients on corporate compliance and governance matters, and litigates civil and white-collar health care fraud cases. You can reach David at (202) 844-3256 or dtraskey@garfunkelwild.com.

Caroline

Guest Blog by David Traskey

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (“CMS”) has paid billions of dollars in reimbursement over the past year to providers using “skin substitutes” to treat patients. Consequently, providers who specialize in treating patients for complex, hard-to-heal wounds are facing growing scrutiny from government regulators over the use and exorbitant cost of these products.

In June, the U.S. Department of Justice’s 2025 National Health Care Fraud Takedown (“Takedown”) highlighted ongoing government enforcement efforts to disrupt or stop purported fraudulent activity involving skin substitutes.[1] Physicians in many specialties (e.g., dermatologists, podiatrists, plastic surgeons, and others who specialize in wound care) as well as other types of advanced practitioners (e.g., nurse practitioners, advanced practice nurses, and physician assistants) (collectively, “providers”) must all be aware of the various ways that they can – however unwittingly- become involved in arrangements that may trigger liability under the Anti-Kickback Statute (“AKS”).

In my experience, the majority of providers are committed to rendering medically reasonable and necessary care to their patients, as well as properly documenting, coding, and billing such items or services to Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial payors. How then do providers get involved in skin substitute schemes such as those described in the Takedown? A small percentage of providers will knowingly violate the Anti-Kickback Statute, the Civil False Claims Act, and/or the Civil Monetary Penalties Law regardless of the possible consequences, so warnings are unlikely to deter them.

Other providers may become entangled in such schemes inadvertently. Providers who are genuinely motivated to render the best possible care for their patients may view certain skin substitute products as both beneficial for patient outcomes, and as a way to improve the financial viability of their practices. This is where caution is essential—the old saying still applies: “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.” How do you determine what arrangements are “too good to be true?” The devil is always in the details.

There are many entities in the skin substitute space including patients, providers, manufacturers, distributors, wholesalers, sales representatives, marketing agents and payors – to name only a few. With so many players operating in the same space, often in connection or consultation with each other, contractual arrangements are common. Well-intentioned providers may nevertheless wonder, “How can things go wrong if I have a contract”? One surefire way is if you, as a provider, sign a contract without fully understanding it. Many of these contracts are not drafted to protect the provider’s business or personal interests. Another way things may go wrong is if you do not understand how or where you fit into the bigger picture with all these different players.

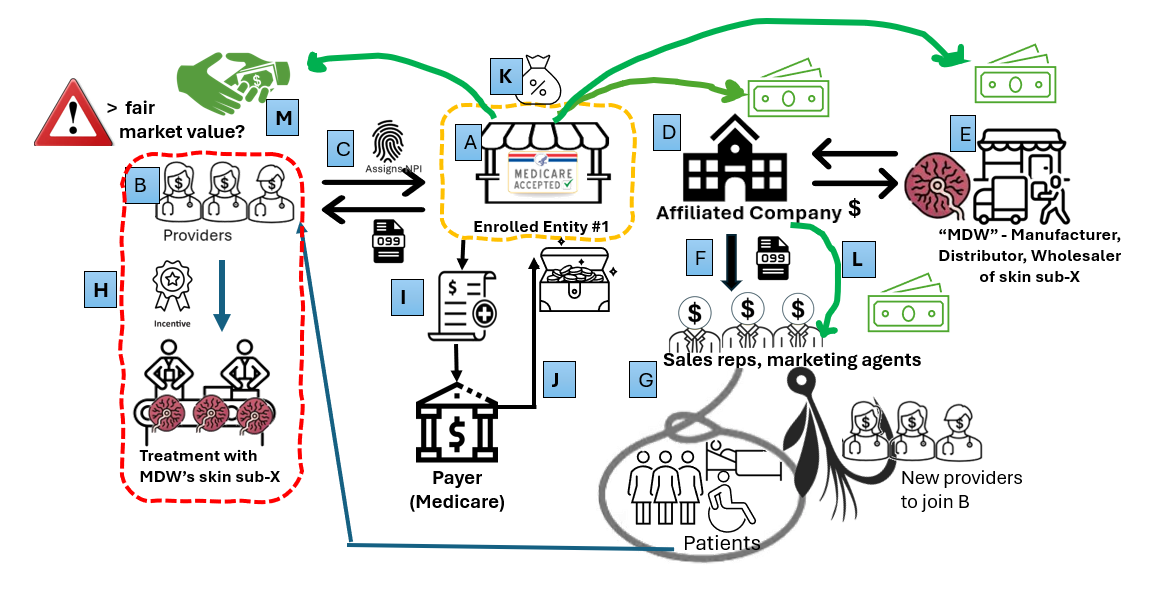

This diagram illustrates the complex arrangements among entities in the skin substitute market and provides but one example of how providers may become involved in high-risk situations unintentionally. Let’s walk through a hypothetical example:

This diagram illustrates the complex arrangements among entities in the skin substitute market and provides but one example of how providers may become involved in high-risk situations unintentionally. Let’s walk through a hypothetical example:

(A) Enrolled Entity #1 is a Medicare-enrolled organization that contracts with providers as 1099 independent contractors (B). These contractors reassign their billing privileges to Enrolled Entity #1 (C). Enrolled Entity #1 also owns an affiliated company (D) that purchases skin substitute products from (E), a manufacturer, distributor, or wholesaler (“MDW”). The affiliated company hires sales representatives and marketing agents (F) to arrange for—or recommend—the purchase of MDW’s skin substitutes by Enrolled Entity #1’s independent contractors. These sales representatives and agents may also recruit additional providers to join Enrolled Entity #1 as independent contractors and solicit patients to participate in the scheme (G). The representatives or agents then steer patients to the independent contractors, regardless of whether the patients have a legitimate medical need for skin substitute treatment.

Enrolled Entity #1’s independent contractors may see the recruited patients (or not) and bill for services, including the use of skin substitutes (H). Enrolled Entity #1 then submits claims that used MDW’s skin substitute products to the payor (most often Medicare) on behalf of the independent contractors (I) and receives payment (J). Enrolled Entity #1 takes a cut of these payments, and then pays the MDW, its independent contractors, and the affiliated company (K), which in turn compensates the sales representatives, marketing agents, and/or recruiters (L).

This arrangement can function even without reassignment of billing privileges. Given that some skin substitute products now cost more than $2,000 per cm², the financial incentives are substantial. Compensation or bonuses in these schemes frequently exceed “fair market value” or “commercial reasonableness,” as they are tied to the volume of business or value of referrals (M). The government’s long-standing position, as reflected in the Takedown summaries, is that payments based on the volume of business or value of referrals are inherently suspect, and will trigger scrutiny and potential liability under the AKS. The resulting overutilization and provision of items and services, often without adequate or any documentation of medical necessity, imposes enormous costs on patients, federal health care programs, and commercial payors alike. Such actions also cause other providers working in this space to be unduly investigated.

Other “too good to be true” red flags include:

- Reassigning your billing privileges without getting written confirmation that the entity submitting claims under your NPI will do so only for the services you personally perform.

- Receiving patient referrals from providers with whom you have no prior relationship.

- Receiving patient referrals from sales representatives, marketing agents, or recruiters.

- Treating patients with whom you have no prior relationship (e.g., applying a skin substitute on the initial patient encounter).

- Receiving compensation that is not commercially reasonable and/or exceeds “fair market value” for your services.

- Receiving compensation or bonuses based on the volume of patients you treat or the value of the referrals you make.

- Being asked to generate medical records for a patient that you did not personally treat or that you have never treated.

- Being asked to generate or maintain two different sets of “books” or invoices or being asked to underreport financial information.

- Providing care that is not medically reasonable or necessary, including that which stems from kickbacks or prohibited referrals, results from patient steering, or causes over-utilization.

The stakes have never been higher for providers who use skin substitutes in patient care. Government regulators are actively auditing and investigating skin sub claims using advanced data analytics and other tools and are clawing back money paid to providers. However, audits and monetary claw backs might be the least of a providers’ worries. Other potential adverse outcomes include state licensure and/or disciplinary actions as well as criminal prosecution and the loss of your freedom.

Providers should not face these challenges alone. In addition to your clinical staff, it is vitally important to have a team of attorneys, medical necessity experts, and billing, coding, and documentation specialists to assist you at each step. It’s also a good idea to remember that “if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.”

Related posts:

- Arizona NP Pleads Guilty to Medicare Fraud Over “Skin Substitutes” – Caroline Fife M.D.

- Two Nurse Practitioners Charged in Connection with APX Scheme with Fraudulent Application of Amniotic Products – Caroline Fife M.D.

Dr. Fife is a world renowned wound care physician dedicated to improving patient outcomes through quality driven care. Please visit my blog at CarolineFifeMD.com and my Youtube channel at https://www.youtube.com/c/carolinefifemd/videos

The opinions, comments, and content expressed or implied in my statements are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect the position or views of Intellicure or any of the boards on which I serve.