More Evidence for Angiosomal Ischemia in This Report

It’s finally out! The follow-up to the paper published previously about the angiosome theory of pressure injury! Pass this around freely because it was published Open Source.

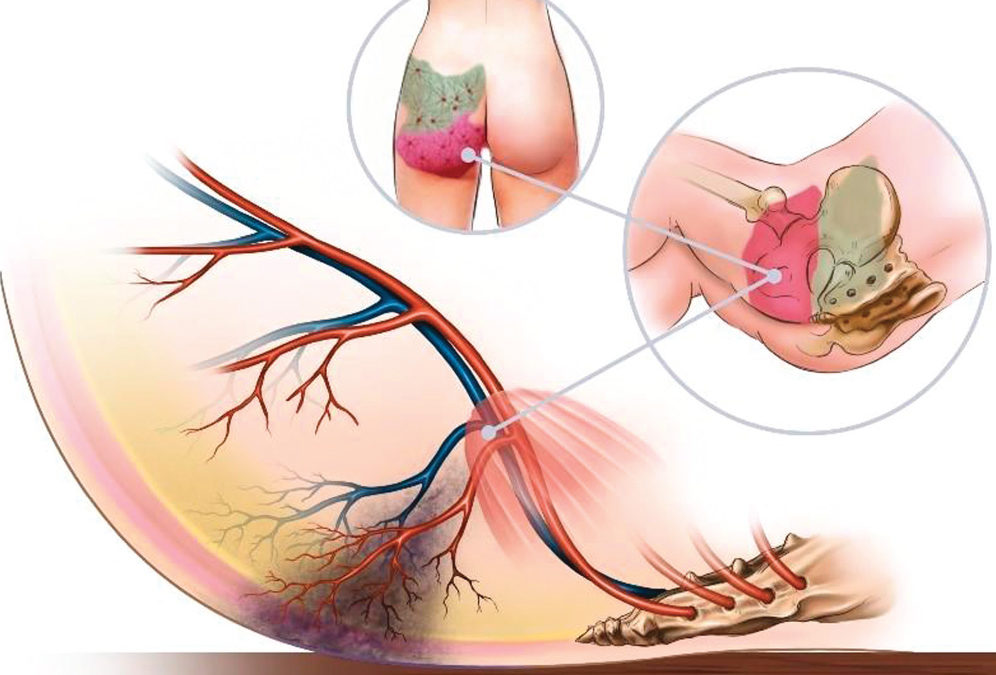

It has never made sense that external compression of capillaries could infarct a large muscle. It’s also puzzled me that severe pressure ulcers nearly always follow the anatomical distribution of vascular “angiosomes,” three-dimensional blocks of tissue supplied by a named artery and vein.

Since the risk factors for severe pressure injuries are mostly hemodynamic in nature, it stands to reason that the key to their formation lies in the vasculature. This patient had the infarction of the fleshy part of the buttocks after several hours of hypotension following coronary artery surgery. I know you have seen similar events, yet the fleshy part of the buttocks do not lie over a bony surface, so how could it happen?

Since his sternum was also breaking down, we made the unusual decision to surgically debride the area before it finished demarcating, in order to apply NPWT and thus reduce wound colonization. Intraoperatively it was obvious that the muscle had infarcted, and there were hematomas on either side of the sacrum, some distance from the visible skin damage, along the distribution of the vessels that supply the buttocks. The obvious conclusion is that the arteries supplying the buttock had thrombosed.

If you haven’t taken gross anatomy, this may not make sense. However, the vessels that supply the buttock come from the abdominal aorta and to get to the backside of the body, they have to pass through the pelvis, exiting the gluteal muscles via some really tight junctions. Some of these vessels are called “perforators,” because they have to pass through the muscle fascia. The weight of a heavy body on those muscles and the vessels that perforate them could result in occlusion of either the arterial or the venous supply to the tissue block. It’s very possible the problem that causes these is occlusion on the venous side, as this is a low pressure zone. It would explain why a low albumin is a powerful risk factor for deep tissue injury. It would also account for why the injuries are so “messy” – not the pale ischemia of an arterial infarction, but the very messy tissue damage caused by engorgement of a vein with subsequent arterial inflow obstruction.

At last, I feel I finally have an explanation for the death of muscles in a predictable pattern in severe DTIs/Stage 4. I think this also explains “stage 1” pressure injuries, which are ischemia reperfusion injuries. I talk about this in a previous case report. The backstory is that I was working on the write-up for the buttock infarction to keep myself busy while waiting for my son to come out of surgery. I had the angiosome “map” open on my computer when my son was brought to his room with several stage 1 pressure injuries. His left lateral foot and right lateral ankle pressure injuries were on areas that had never experienced pressure in the operating room. The only explanation is that they were caused by the wedge at the back of the leg occluding arterial supply to the lateral heel and ankle. That’s when it hit me that both stage 1 and DTIs/Stage 4 lesions were ischemic events – with stage 1 being recoverable ischemia reperfusion events (without tissue necrosis) and DTI/Stage 4 being unrecoverable vascular events.

This idea is not new. More than three decades ago, visionary clinician Roberta Abruzzese suggested that severe decubitus ulcers (the term used at the time) be termed “vascular occlusion ulcers.” She saw the obvious.

I will be posting more about this concept and its implications.

Caroline

Dr. Fife is a world renowned wound care physician dedicated to improving patient outcomes through quality driven care. Please visit my blog at CarolineFifeMD.com and my Youtube channel at https://www.youtube.com/c/carolinefifemd/videos

The opinions, comments, and content expressed or implied in my statements are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect the position or views of Intellicure or any of the boards on which I serve.

Looking forward to see the response!

Vascular compromise as a central factor in formation of injury to the buttocks, natal crease and also, pressure points of the pelvis, is something I have been thinking about quite a lot lately. In fact I think we need to seriously reconsider how we classify some of these injuries where vascular compromise, often in the absence of pressure, is promoting injury. This effort has already begun with the use of the term ‘skin failure’ which has yet to be recognized by ICD10, Medicare and, to my knowledge, any official body outside the wound specialty literature (please correct me if I am wrong about this).

This is important because if we continue to classify injuries primarily vascular in nature as”pressure” while not occurring from pressure, but rather, primarily, from hemodynamic and metabolic factors, we continue to keep ourselves open to financial losses and misplaced litigation.

In our institution, we have seen injuries in our critically ill patients, in a pattern starting at the natal crease, in the context of hemodynamic instability, acidosis, and now, apparently potentiated by the metabolic changes in prolonged hypoxia associated with SARS CoV-2. Due to fairly heavy oversight of wound services in our hospital, along with frequent use of photographic documentation, we have been able to follow several of these patients from early on in the evolution of these injuries. Eventually they may have a pattern that is similar to that seen in “classic”pressure injury (ie injuries where pressure is the primary factor ) but these injuries do not originate over pressure points.

In my documentation, I detail how these injuries are consistent not with pressure but with “skin failure“, but there is no way to code them in ICD 10, except as “open wound“. We need to lobby to expand our billing language to reflect this (and thank you if this is already happening).

The language with which we are able to describe these injuries carries huge implications for how we move forward and classify these injuries, which, in turn influences both how hospitals provide education for both staff as well as patients and families about preventable and non-preventable causes of these types of injuries as well as how we evaluate accountability for them.

As usual, thank you for leading the discussion.