–Caroline

Sea Turtle Fibropapillomatosis: The Role of the Lymphatics

Clinicians who treat patients with lymphedema are aware that the condition can result in dramatic skin and soft tissue changes such as these seen on the lower extremity of a woman in Haiti with lymphedema due to filariasis, a parasitic form of lymphedema spread by mosquitos. The chronic inflammatory state of lymphedema leads to the proliferation of skin and subcutaneous tissue which is called Fibropapillomatosis (FP) . (Here’s a link to the taxonomy of skin changes in patients with lymphedema.)

Humans are not the only species to experience this. Green sea turtles are susceptible to FP, and as you can see in the photograph on the right, it looks a lot like human FP!

When I first saw FP in turtles, I immediately thought it was due to lymphatic impairment (much like the human patients who I see). I reached out to the Nova Southeastern (NSU) Oceanographic Center to discuss my theory. The prevailing belief in marine biology is that FP is caused by the herpes virus. My hypothesis is that the turtles are exposed to contaminated water and food due to pollution and agricultural run-off which impairs their lymphatic system function. To determine the causative factors for FP in sea turtles, I am collaborating with Dr. Berkholder from the Oceanographic Center, Dr. Milton from FAU, and Drs. Eva Sevick and John Rasmussen from The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHSC) as well as Gumbo Limbo with Dr Maria Chadham and Whitney Crowder and UF Marineland sea turtle hospitals.

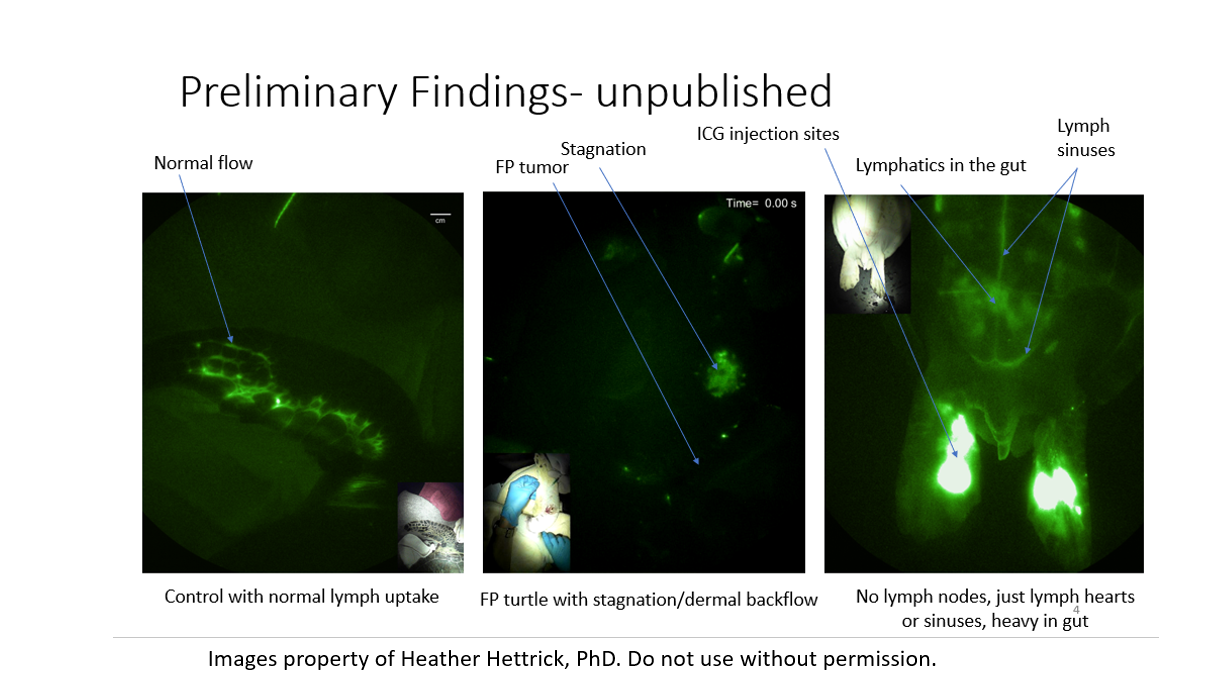

First, we had to start with imaging turtle lymphatics because very little is known about this system in turtles. We did this using Indocyanine Green (ICG) with Near-infrared imaging (NIRFI) thanks to Dr. Eva Sevick and her team at UTHSC. (Find more information about NIRF imaging here).

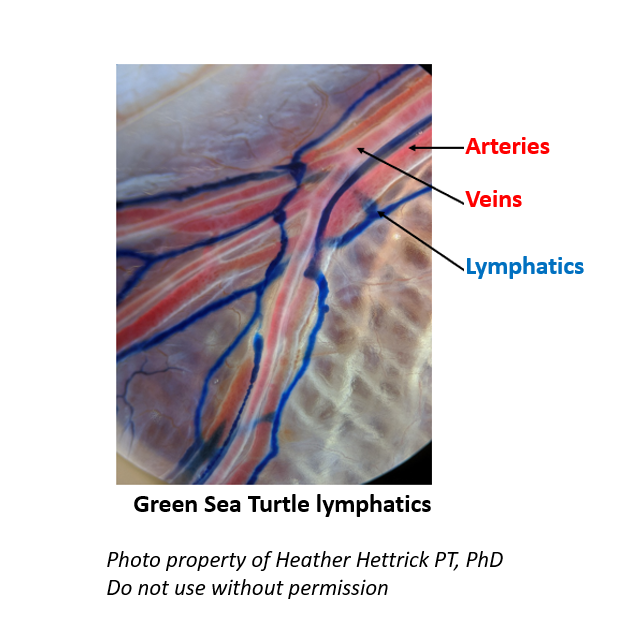

Embryologically, in both humans and sea turtles, the lymphatic system develops from the venous system. We think of the blood circulatory system and the lymphatic system as being separate, but they are closely inter-related. In this photo, the first imaging of sea turtle lymphatics, you can see the arteries and veins surrounded by the lymphatic capillaries (dyed blue from the contrast). This relationship is consistent across many species, although the exact structure can be a little different.

Above is a series of images depicting the sea turtle lymphatic system. Although the lymphatics of turtles look different from humans, in normal turtles, the fluid is still contained in lymph vessels, as seen in the image on the left in a normal sea turtle. The middle image shows stagnation or congestion that we call dermal backflow in an affected turtle. (“Dermal backflow” is also seen in women who develop lymphedema after treatment for breast cancer.) This same congestion also happening near an FP tumor, indicating the connection between the lymphatics and the integument in turtles affected by FP. The image on the right shows how the lymph fluid in turtles drains into “lymph hearts” or sinuses rather than lymph nodes, as it does in humans. In humans, the lymph nodes are where lymphatic fluid is cleansed and processed before re-entering the venous system – but clearly, turtles do not have these structures. In the turtle, we believe these sinuses dump the lymphatic fluid directly back into the circulatory system and that turtle lymph fluid may be cleansed in the gut lymphatics; concentrated centrally in the image.

This research is still ongoing. However, I encourage all clinicians to keep their eyes open. The marine biologists who care for these turtles had never seen fibropapillomas in humans and thus had no framework to interpret what they were seeing. In this case, human pathophysiology may provide the needed insight for marine biologists. Thank you to all my collaborators in this ongoing research!

Heather Hettrick PT, PhD, CWS, AWCC, CLT-LANA, CLWT, CORE

Professor

Admissions Committee Chair

Faculty Residency Mentor

Experiential Learning Fellow- NSEE

Dr. Fife is a world renowned wound care physician dedicated to improving patient outcomes through quality driven care. Please visit my blog at CarolineFifeMD.com and my Youtube channel at https://www.youtube.com/c/carolinefifemd/videos

The opinions, comments, and content expressed or implied in my statements are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect the position or views of Intellicure or any of the boards on which I serve.

very very interesting!!!