The CDC continues to warn about the increasing incidence of both active and latent tuberculosis (TB) in the U.S. population and has asked all physicians to be on the alert for cases. Since all chronic non-healing wounds are a symptom of a disease, wound practitioners often find themselves in an unwritten episode of the TV show “House,” searching for the mysterious cause of a patient’s symptoms. Today when I saw the renewed CDC warnings, I was reminded of the biggest missed diagnosis of my career. In my defense, it was way back in1992, which is why these photos are of such bad quality. They were originally taken with a Polaroid camera and have been copied from one media to another over the years. I have kept this case to remind me of my big mistake, and in hopes that other clinicians can learn from my mistake.

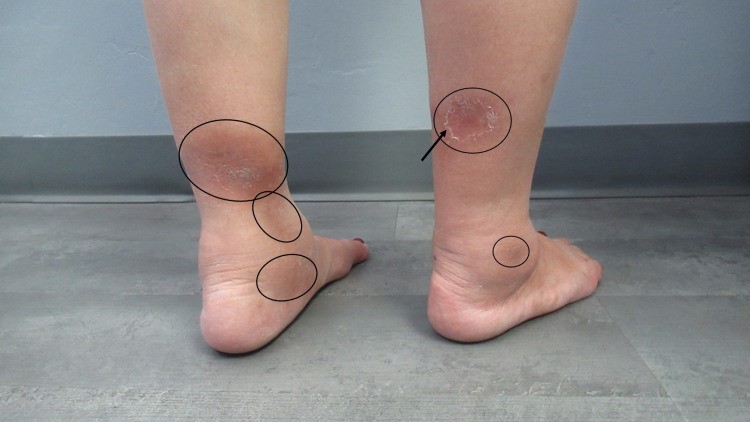

The photo above is of a 59-year-old woman with adult onset diabetes and end stage renal disease on dialysis. She had undergone a biopsy of a left thigh lesion three weeks before and was referred to me at the wound center for a non-healing ulcer at the site of the biopsy. The biopsy had showed erythema nodosum (EN).

I fiddled with the enlarging wound created by the biopsy for several months (remember, I was young and had only been running a wound center for 2 years) but finally called my dear friend Dr. Adelaide Hebert in the Dermatology Department of the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston. I am proud to add that Dr. Hebert ultimately taught me nearly everything I know about chronic wounds. This case was only one of the countless times she came to my rescue and the rescue of my patients.

Dr. Hebert asked me if I’d gotten a chest X-ray on the patient, to which I said, “And why would I do that?” She replied, “Because erythema nodosum is sometimes associated with an active TB infection.”

You guessed the rest. The patient had a suggestive chest X-ray and after that, a clearly positive sputum sample for the acid fact bacilli of TB. She had been in and out of the waiting room and exam room for months, and the hospital infectious disease team had to trace every person who’d been in the waiting room at every visit, not to mention all of the hospital staff. It was a huge project. Thankfully, no other cases of TB were identified, but I am pretty sure that no one in hospital infection control talked to me for at least a year.

My photos don’t show you what erythema nodosum usually looks like, so I’ve included one from this article about Tb related EN. As you can see, the lesions are not very impressive and could be mistaken for stasis changes (except that they are nodular and often painful). EN rarely presents as an open wound. In my patient, the wound was due to the biopsy itself which failed to heal for a host of factors of which TB was only one.

My mistake was what I missed was the association of EN with active TB. The incidence of tuberculosis-associated erythema nodosum, from a review of several retrospective erythema nodosum studies, is only 6%. However, the incidence of tuberculosis is higher when individuals with secondary erythema nodosum are included (11%) or infection-associated erythema nodosum (21%) are included.

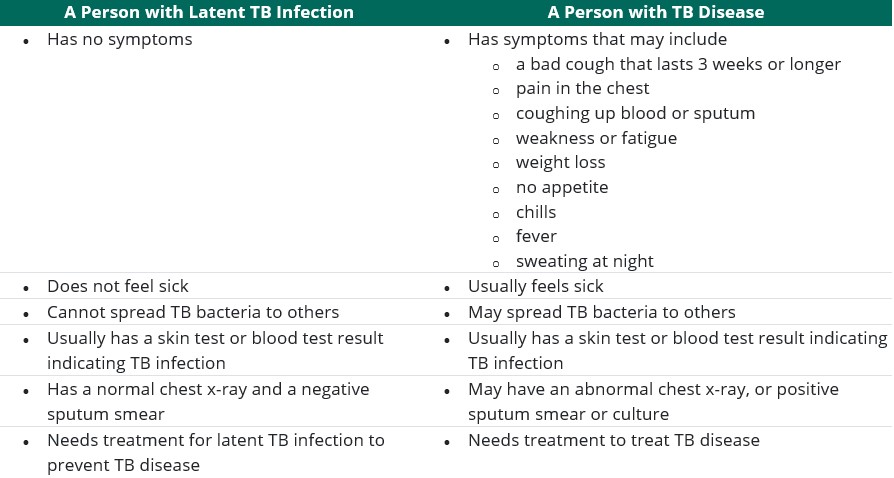

I’ve provided below the table from the CDC listing the possible symptoms of TB. You can see why we are having trouble stopping the spread of this disease in the U.S. My patient had a history of a chronic cough (although I don’t remember every noticing her cough during a visit), low grade fever, and fatigue – all of which are non-specific. However, I bet I’d have paid more attention to her non-specific complaints if I’d been paying attention to the differential diagnosis of erythema nodosum.

I keep these grainy, poor quality photos from 1992 in order to remind me of the painful and humbling lesson I learned about the association between EN and TB, and why wound care practitioners need to be the most intellectually curious of all clinicians. The most powerful diagnostic tool we have is the question, “Why?”

The Difference between Latent TB Infection (LTBI) and TB Disease

Dr. Fife is a world renowned wound care physician dedicated to improving patient outcomes through quality driven care. Please visit my blog at CarolineFifeMD.com and my Youtube channel at https://www.youtube.com/c/carolinefifemd/videos

The opinions, comments, and content expressed or implied in my statements are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect the position or views of Intellicure or any of the boards on which I serve.